SRSD Theoretical Integration Enhances Learning Outcomes

In the previous blog, we explored the history of SRSD (Self-Regulated Strategy Development). This blog will continue the SRSD story and how Karen Harris integrated multiple educational theories, including behavioral theory, cognitive psychology, and sociocultural theory. This process, known as theoretical triangulation, allowed SRSD to become a comprehensive instructional model for teaching writing, incorporating various perspectives through modeling techniques and educational strategies, now known as the Science of Writing.

These blogs were written from Karen Harris’ Study: The Self-Regulated Strategy Development Instructional Model: Efficacious Theoretical Integration, Scaling Up, Challenges, and Future Research, published in September 2024.

Theoretical Integration and Triangulation in SRSD: Building a Multi-Dimensional Model for Writing Instruction

By combining insights from different theories, self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) provides a powerful approach to teaching students not only how to write but also how to self-regulate their learning through goal setting, self-monitoring, and self-reinforcement—pioneering a comprehensive form of writing instruction and strategy instruction. The blog highlighted how SRSD equips students with cognitive, emotional, and behavioral tools critical for managing complex learning tasks and enhancing their self-efficacy—a key component of social-emotional learning and literacy. It is a multi-dimensional model that can be adapted across various subjects and learning environments.

Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) has been described as a model of instruction that integrates multiple theoretical perspectives, providing a rich approach to pedagogy focused on comprehensive writing instruction. But what does that mean, and how does it work? In this second part of our blog series, we will explore the theoretical underpinnings of SRSD and the process of theoretical triangulation that allowed it to become a multi-dimensional model for teaching writing.

In this video, Karen Harris tells us more about how she combined psychological theories to help make SRSD for writing what it is today:

The Need for Theoretical Integration to Boost Genre-Based Writing

Like many fields, educational psychology has seen the proliferation of multiple theories attempting to explain the same phenomena. Karen Harris, the principal creator of Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD), recognized that only some theories could adequately address the complex needs of struggling writers, including those with learning disabilities. Instead of committing to one theoretical framework, she sought to integrate the most effective elements from various theories to create a more robust instructional model.

In a 1982 paper, Harris outlined her belief in the importance of evidence-based SRSD theoretical integration. She argued that different theories offer unique insights into teaching and learning and that by combining these insights, educators could create a more robust and practical approach to instruction. This philosophy became the foundation of SRSD, which draws on behavioral theory, cognitive psychology, sociocultural theory, and more to support students in developing self-regulation and writing strategies.

The Concept of Theoretical Triangulation

One of the most important ideas behind SRSD is theoretical triangulation. Theoretical triangulation occurs when similar or identical teacher and student actions are described differently across multiple theories. Educators can create instructional practices supported by numerous research lines by identifying these commonalities.

For example, several theories emphasize the importance of scaffolding in learning. Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) concept describes how students can achieve more with guidance from a knowledgeable person than they can independently. Similarly, behavioral theory introduces the idea of successive approximations, where students are supported in small steps toward a goal. Additionally, the gradual release of responsibility model in educational psychology describes how teachers initially lead instruction before gradually shifting responsibility to students.

Although these theories use different language to describe the scaffolding process, the underlying actions are the same: a teacher or knowledgeable peer supports the student, who gradually takes on more responsibility for their education and learning. This theoretical triangulation reinforces the importance of scaffolding as a critical component of Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) writing instruction.

Core Tenets of SRSD Theory Development

Several core tenets emerged as Harris integrated multiple theoretical frameworks into Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) and writing instruction. These principles guided the model’s development and continue to shape its evolution today through SRSD theoretical integration and strategy instruction.

Why is SRSD theoretical integration important?

Theoretical integration in SRSD (Self-Regulated Strategy Development) is essential for several reasons:

1. SRSD is a Comprehensive Approach to Learning

Theoretical integration allows SRSD to draw from multiple educational frameworks, such as cognitive psychology, behavioral theory, and sociocultural theory. This creates a more holistic instructional model that addresses the various dimensions of learning—cognitive, emotional, and social. By leveraging different theoretical perspectives, SRSD can better support students in managing the complexities of writing and other academic tasks through The Science of Writing.

2. SRSD Addresses Diverse Student Needs

Each student brings unique strengths, challenges, and backgrounds to the classroom. The integration of theories ensures that SRSD is adaptable and flexible, incorporating various educational strategies to meet the diverse needs of learners. Whether students need help with cognitive processes like planning and organizing their writing, writing instruction, or emotional support to build self-efficacy and motivation, SRSD’s integrated framework provides strategies that address multiple aspects of learning.

3. SRSD Enhances Self-Regulation

By combining theories, SRSD strongly emphasizes self-regulation, teaching students not only what to do but also how to manage their learning process through effective writing instruction. Integrating cognitive and behavioral theories allows students to develop essential self-regulation strategies, such as goal setting, self-monitoring, and self-reinforcement, which are critical for long-term success in writing and other tasks and foster social-emotional learning.

4. SRSD Maximizes Learning Outcomes

Theoretical integration in SRSD amplifies its effectiveness. SRSD research shows that interventions that integrate multiple theories, including the science of writing, often substantially impact student outcomes more than those based on a single theory. SRSD’s ability to blend concepts such as scaffolding from sociocultural theory and self-regulation from cognitive-behavioral theory has yielded significant improvements in writing quality, student motivation, and overall academic performance.

5. SRSD Promotes Flexibility Across Subjects

Using integrated theories makes SRSD applicable beyond writing and enhances literacy across different subjects. The principles of SRSD, mainly its focus on self-regulation, can be adapted to other academic areas like reading comprehension, mathematics, and science. This flexibility stems from the theoretical foundation that addresses general learning processes, making SRSD versatile across subjects and educational contexts.

6. SRSD Supports Equity and Inclusion

Because SRSD incorporates elements from diverse educational theories, it is more inclusive in addressing the needs of all students, particularly those who may be marginalized due to learning disabilities, language barriers, or socioeconomic factors. Integrating multiple perspectives ensures that SRSD promotes equity in the classroom by providing instructional methods that can benefit a wide range of learners.

The theoretical integration behind SRSD is critical because it enhances the model’s adaptability, comprehensiveness, and effectiveness, allowing it to meet students’ diverse and complex needs while maximizing their learning outcomes across various subjects through evidence-based practices.

No Single Theory Can Provide All the Answers

Harris believed that no single theory could fully address the needs of diverse learners, particularly those marginalized by poverty, race, learning disabilities, and disability. By integrating multiple theories, SRSD provides a more comprehensive approach to instruction.

All Students Deserve Effective Instruction

Harris’s early teaching experiences with students in impoverished communities reinforced her belief that marginalized students deserve high-quality instruction. Self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) was designed to meet the needs of all students, regardless of their background or ability level.

Theoretical Triangulation Enhances Instruction

By identifying commonalities across theories, Harris and her colleagues created a model of instruction that maximizes learning outcomes through improved pedagogy. Theoretical triangulation highlights the importance of teacher-student interactions, scaffolding, and self-regulation in the learning process.

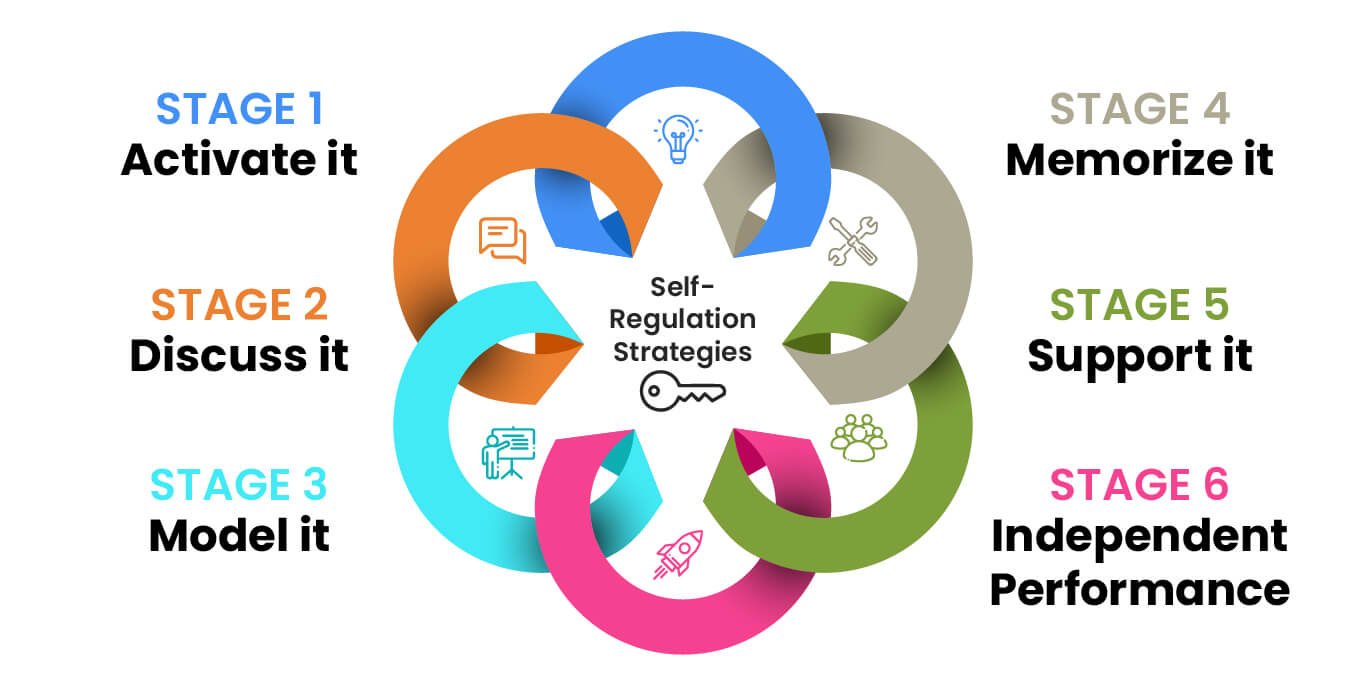

The Role of Self-Regulation in SRSD

Self-regulation is a critical component of SRSD, drawing on research from cognitive psychology, behavioral theory, sociocultural theory, and education. In SRSD, students learn to regulate their writing through goal setting, self-monitoring, self-instructions, and self-reinforcement. These self-regulation strategies are essential for managing the complex demands of writing, which require cognitive and emotional effort.

Harris’s work was heavily influenced by the research on self-regulation conducted by Albert Bandura and Barry Zimmerman. Zimmerman, in particular, developed a model of writing that emphasized the role of self-regulation and modeling in managing the cognitive, behavioral, and motivational aspects of writing. His research demonstrated that students who actively regulate their writing process and develop strong self-efficacy are more likely to produce high-quality work and persist through writing challenges.

In SRSD, writing instruction emphasizes self-regulation, teaching it explicitly through strategies like goal setting and self-monitoring. For example, students might set a goal to use a specific number of genre elements in their writing and then monitor their progress toward that goal as they work. They are also encouraged to use positive self-instructions to stay focused and motivated. These self-regulatory strategies help students become more independent writers, capable of managing their writing process.

Metacognition and Executive Function in SRSD

In addition to self-regulation, self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) incorporates metacognition and executive function concepts. Metacognition in pedagogy refers to students’ awareness and control of their thinking processes. In writing, metacognition involves knowing when and how to use different writing strategies and being aware of one’s strengths and weaknesses as a writer, which is a crucial aspect of education.

Research on metacognition has shown that students with a strong understanding of their cognitive processes, including those with learning disabilities, can better plan, monitor, and revise their work. Self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) explicitly teaches students to develop metacognitive awareness by helping them build declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge about writing. Declarative knowledge refers to knowing what to do (e.g., the steps in the writing process), procedural knowledge refers to learning how to do it (e.g., using a specific strategy), and conditional knowledge refers to knowing when and why to use specific strategies.

Executive function, on the other hand, involves the conscious activation and management of strategies, knowledge, and motivational states to achieve a goal. In writing instruction, executive function is critical for planning, decision-making, and attention control, supported through self-regulated strategy development. SRSD instruction supports the development of these executive function skills by teaching students how to break down complex writing tasks into manageable steps and apply the appropriate strategies to complete those tasks, incorporating strategy instruction, the science of writing, and enhancing self-efficacy as a critical component.

Integrating Behavioral and Sociocultural Theories

Another critical aspect of SRSD’s theoretical integration is its combination of behavioral and sociocultural theories, particularly B.F. Skinner’s work on reinforcement and punishment plays a significant role in SRSD’s approach to self-regulation. However, SRSD does not rely on tangible reinforcers like rewards or punishments. Instead, it emphasizes social reinforcement to motivate students, such as feedback, praise, and a sense of accomplishment.

At the same time, SRSD draws heavily on sociocultural theory, particularly Vygotsky’s ideas about the social origins of learning. Vygotsky argued that learning is inherently social and that students learn best through interaction with a more knowledgeable other. In SRSD, collaboration between students and teachers is a central instruction feature. Teachers model writing strategies and self-regulation techniques while students work in pairs or small groups to practice and refine these skills, engaging in modeling to demonstrate effective writing strategies.

Integrating behavioral and sociocultural theories allows SRSD to address both the cognitive and social dimensions of learning, including incorporating social-emotional learning to support student development better. By combining these perspectives, SRSD provides a more comprehensive and flexible approach to teaching writing, incorporating various educational strategies to enhance student outcomes.

SRSD: A Multi-Dimensional Approach to Writing Instruction

The theoretical integration and triangulation behind SRSD make it a uniquely powerful model for teaching writing and improving literacy. By combining insights from behavioral theory, cognitive psychology, sociocultural theory, and more, SRSD addresses the full complexity of the writing process. It empowers students to regulate their learning, develop metacognitive awareness, and use executive function skills to tackle writing challenges, providing essential writing instruction.

In the final part of this three-part series, we will explore the practical application of SRSD in the classroom and discuss how teachers can implement this model to improve student writing outcomes. This includes the role of writing instruction and the expanding role of its evolution, making SRSD The Science of Writing.

About the Author

Randy Barth is CEO of SRSD Online, which innovates evidence-based writing instruction grounded in the Science of Writing for educators. Randy is dedicated to preserving the legacies of SRSD creator Karen Harris and renowned writing researcher Steve Graham to make SRSD a standard practice in today’s classrooms. For more information on SRSD, schedule a risk-free consultation with Randy using this link: Schedule a time to talk SRSD.